I learned to read around three or four. A neighbour child had a small schoolhouse in the hard and would gather up all the littler ones to teach us. I grew up in a house full of books, so playing school, in which all I did was sit around and read things, well, let’s just say I showed up.

It was surprising to my parents to realize I could read. I was mimicking my father and sitting at the table reading the paper, perusing sections, pausing, and a comment was made about how cute it was that I was turning the pages, so I started reading aloud. My mother was a library, and my older brother was learning to read in kindergarten, so there were always books.

I cannot remember a time without books. We had abridged editions of the classics as kids, The Count of Monte Cristo was my favorite, and second, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. I read all the books in our house, and quite a few in the neighbours as well, as they owned an Encylcopedia Britannica, and I’d go over on Saturday mornings after I wasn’t needed for anything else, and slowly read it from start to finish. By mid-highschool I had read all the books in the library. For those who do not recall small town libraries full of paper books, there was a particular section on criticism that fascinated me. It also bored me. Who thought so much and like this, that they wrote these things?

In my third year of highschool I took a part time job at a used bookstore. Small wages, but I was allowed to borrow and read any book I wanted, I just had to return them. A new lending library that had a lot more trash in it than the town library, mysteries, murders, policiers, romances. I read them all, though I was more embarrassed by these and reading of things such as Harlequin Romances was done as surreptitiously as possible.

As an undergrad, surprising, I am sure, I took on work a few days a week in the library. I worked in interlibrary loan and special collections. I read everything I could get my hands on. Start at this time, I began tracking what I read in old chemistry notebooks. Grey blue covers, yellow lined and numbered pages, hard covered. Every book, my thoughts, other things to read, words I had learned, I kept these for perhaps 20 years, until the manufacturer discontinued them. I tried several new formats, similar structures, but none really ever did the trick. The same company makes them again but the texture of the cover is different and they are purple. I have quite a few that are blank, bought in hopes that I would restart, but the new format never caught on. Reading back on the old ones, there is a lot I had forgotten, but it is also interesting to see who I was, what I was thinking, what I was reading.

When I graduated from undergrad and moved to SF I was too poor to buy books. I always had been, but I had always had libraries. Now I was without and needed to be careful about spending. I lived around the corner from a bookstore, and allocated a purchase a book a week.

I was, for some reason, very curious about the meaning of the world, my role in it, if there was some way of knowing anything. I read classics, philosophy, history, mysticism, religious studies, and physics and maths books. I borrowed from those who would lend, bought what I could, and spent, according to these notebooks, two years trying to answer questions. One day, I stopped. I decided I would never be able to answer questions and truly know, so reading these was not necessary. I didn’t stop pondering and considering, I just stopped pour dense and complicated things into my soul.

My upstairs neighbours read Chandler and noir, so I borrowed from them. The man around the corner gave me my first Calasso book, opening that thread that continues til this day. San Francisco in the early 90s was full of so many curious people, that my book borrowing habits covered anything and everything. Those days, if you remember, not only did we read, we sat around and talked about them til all hours. My friend Dino and I, in particular, skinny 20 somethings on motorcycles, would meet up at bars in the afternoons to talk about philosophy or theory or design or art.

This pattern continued, but also, modified. I started reading in ‘chunks’, books that felt related to each other in some way so I was getting many points of view at the same time, synthesized down into what I hoped was a more rounded experience of whatever topic obsessed me. I started to buy books, and for most of my early adult life they were shelved geographically. I had an enormous India section, and for a long time, Albania, South Africa, and others. Pull a thread on the sections the the questions tumbled out, what drove me in that direction.

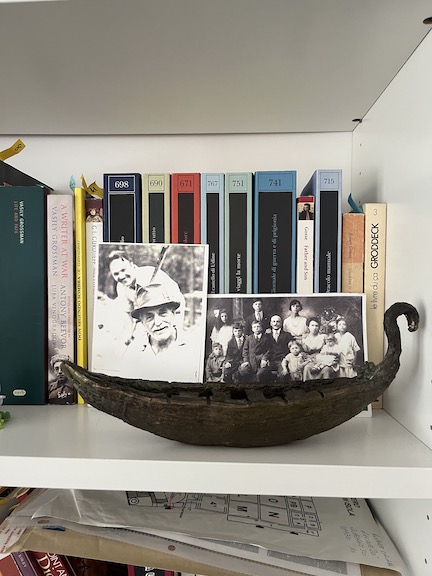

These days my books are not really shelved, and they are certainly in no order, except the occasional shelf here and there. There are selves on south asian religions, and a chunk of buddhism. The Adelphi books, of which I have over a thousand, core and related, are generally close together. But sometimes they are order publication number, and sometimes by author’s last name. There are troubles though, the Blixen Dinesen and similar issues where different names appear in different countries.

Today there are at least a hundred books around me in stacks, the shelves are a disaster, the books are spread across five rooms and, at last count, there are 28 book cases in this house — not all books are mine.

For most of my life I have preferred to read a book in a single sitting. This is good and bad. The single sitting experience is immersive and obsessive, I get so far deep into the thing, that I can’t stop. Literally, no matter how insane it might be, I stay up til two or three in the morning. I was indeed that child with a flashlight hiding away to not stop reading, but I don’t remember my parents caring much. As long as I was out the door in the morning on time, and didn’t sleep during the day, there was a big of a shrugging sensation. I am a gen x kid though, so it could just have been the time.

Digital books make obsessive reading worse. It is easier to pass out with a paper book on my face than break me away from a device. I try not to read on devices, but this past year I made that harder, by deciding that I would buy no books for a year — in any format. I had a library card, but I found Libby, so now I can read too late, and in general it is bad.

At the end stages of my PhD — I can’t help but want to create a terminal capitalism like phrase for what this is, the closest I get is to describing it as a state of thesis psychosis, I read papers and books, or re-read bits of them when I am looking for things, or I read sorbet. Sorbet, the books I can forget as soon as I read them, because the reason I read them is to not be present in my life, or in my thesis, to give pause. It reminds me of the limoncello granita one finds in Amalfi, which might be a better choice for some reasons, but worse for many others.

My thesis is due in 159 days now, draft sooner, books don’t really need to be read for that, but sometimes I use them to forget. Not buying books is a lot easier than I expected. Even though there are books I would have bought, earlier me, unbridled version, I feel a bit thankful that I don’t need to buy them and read them now, as it is disallowed. Oh, and for the record, I read the books I buy. Because I can’t help myself.

A few years ago W. tried to calculate how many books he had left to read in his life, based on his pace and his life expectancy. It was very low, I think he decided at the high end it would be 2000. This might not seem low, but there were years, especially Adelphi years, where I read over 300 books a year. Mortality and Morbidity report suggests I have far more than six years to live, though given the state of the US today, those numbers may start trending down faster than they have been.

But where was I? Oh yes, the ease with which I do not buy books, even though I still go in bookstores and read the covers and sometimes some of the books. I take their pictures, too, as though I will take the book from the library or remember to buy it when the year is up.

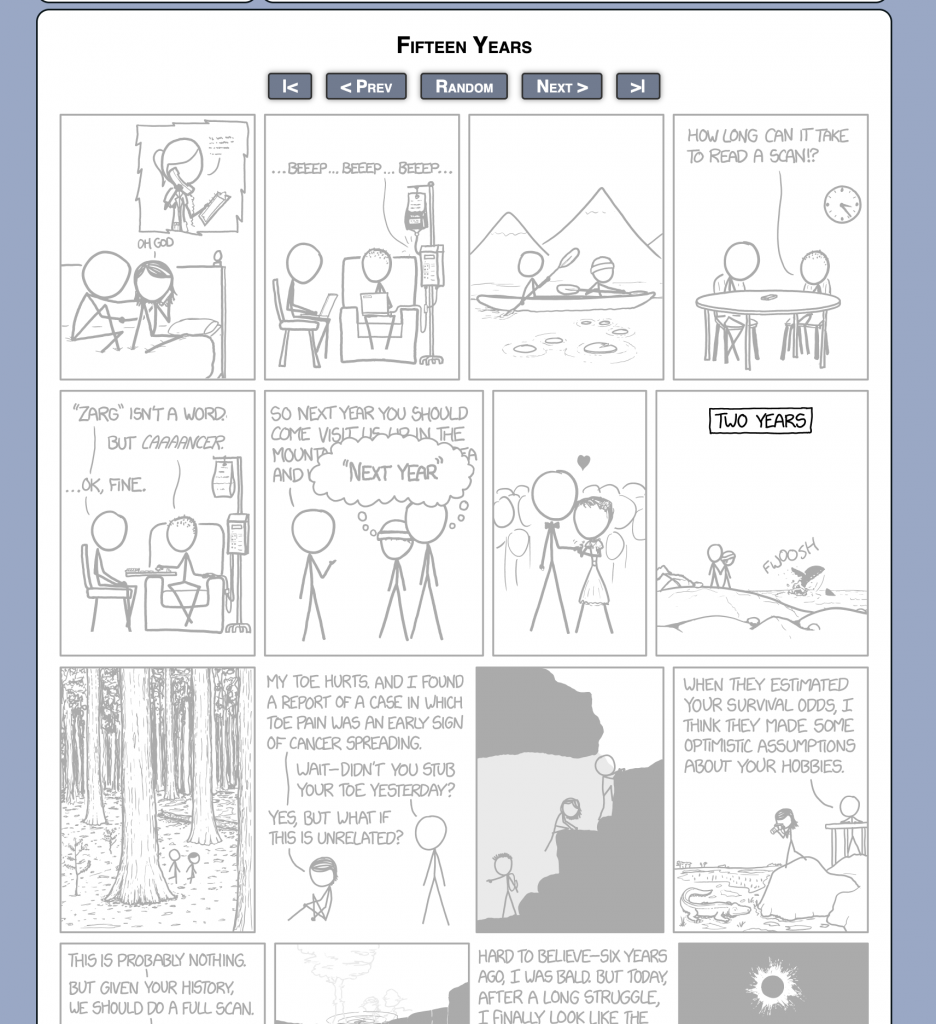

But here’s the thing. Not reading is…pleasant. And not in the way I didn’t read for a year when undergoing cancer treatment. That time, I couldn’t read. I couldn’t think either, and frankly, moving about was hard as well. So I know I can go a year without reading, but I am thinking of doing it again, this time by choice.

I think it will let me slow down, spend more time having other people telling me what they read and what they learned from it — please keep reading, friends. I hope it will get me to spend more time in nature and looking at the sky and the sea. I would have to spend my time differently. I don’t want to replace reading with some mindless act, watching Netflix or baking, or the like.

I don’t what what the rules would be. Could I re-read my book journals from those twenty years? Rethink all the things previously thought? And what about other forms? I can read journal articles? For several years in the mid 2010s I read every journal article on language translation and AI, and wrote about them. That seems ok, more engaged. Can stopping reading books make me more engaged with the world? I think it will.

There are other things I want to make, as well. With my hands, as well as with my mind. I look forward to this, this idea, anyway. But perhaps what I need to be is more discerning and thoughtful about what I read and why. But no, I think it is not that. I feel like I have gotten out of touch with what is within me, my mind and beyond, whatever that is, and the only way to get back to this is to stop adding to it, shuffle back through, unload some things. I get an image, suddenly, of storage wars, and the clean out phase. Perhaps there are too many words me my head, in so many languages, and mathematical equations, and the sounds of squealing pigs (where did that come from?), and I just need it all to find ease in silence again, and then spin back into meaningful shapes, not these fracture unrecognizable monsters.

What would I find in there? Compelled to find out. But first, I must find the escape velocity, decide the laws of physics of my engine, and pack what is necessary. It amuses me to consider blogging the books I did not read, but would consider, if I were reading, with entirely fabricated reviews on non-intervention.

Now I must go reshelve these books, and consider throwing out every piece of paper I have printed in the past two years. Remove, replace, resign, reform. Dance. Yes, let us dance.