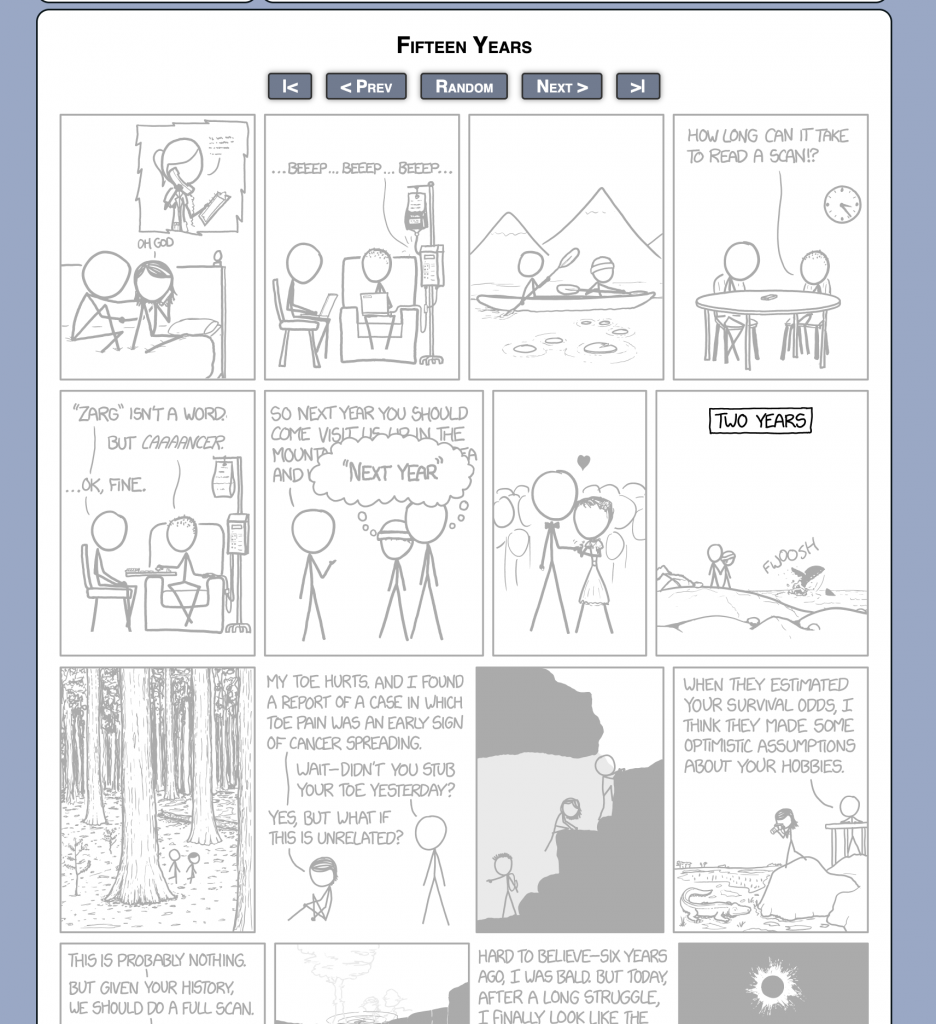

For some reason, this refuses the embed, so the link to the full thing is here.

I laughed when I read this, particularly the estimated odds of survival and optimistic assumptions about hobbies panel. I don’t have any particularly dangerous hobbies at the moment, other than the phd-induced-psychosis, which ought to be in the DSM-5, but I am pretty sure isn’t, and which I shall shortly recover from. I do, however, desire to have more dangerous hobbies. I could use more arctic kayaking expeditions, and definitely a return to scuba diving all over the world. I miss working with bronze sculpting, but I don’t think that really shortens my life span.

I know quite a few people who have made it to the fifteen year mark. I know that five is the one where the doctors look away, but I find fifteen, which I am not far off from, to be more significant. Perhaps because there is more time to look back on what happened AFTER.

After reading this two days ago, I found myself thinking about what I would do differently if I went back to that time period. Not to change the diagnosis, or even the treatment choices (though I might), but how I attempted to put my life back together afterword, what that entailed, and how I did. If I gave myself a grade, it wouldn’t be very high. I’d have failed out and probably in that mode where the teacher takes you aside and says, ‘maybe this subject isn’t for you,’ except of course in this case that subject is life.

Despite being in two of the best cancer hospitals in NYC, and having reasonable health care coverage for America, the aftermath was a shit show. I suspect the process was as well, but as I liked to joke at the time, I was busy with the survival bit, all the rest could wait. Undergoing cancer treatment and living in NYC without paid sick leave decimated my savings and put me into debt. I was in my mid-30s at the time, and had a very nice savings account with which I intended to buy me a flat of my own. Post-cancer, not only was that gone, but I had acquired debt on credit cards. Some was medical debt, some was my radiation survival technique of buy a new dress a week, for six weeks (retrospectively, weird, but ok, that happened).

I was diagnosed with cancer two weeks after I graduated from Columbia Business School. Three weeks before the end of school I had quit my high paying job running CX for AOL Products. The politics were hellacious, the constant end of year reorgs frustrating, and I had been transferred out of working with the product people I loved onto a New York City-based media and content focused team, and the culture shift was agonizing.

There is a lot I’d like to say about the family process of navigating cancer but I’d really prefer everyone I wish to talk about were dead before I do so. Let’s just say that with the exception of spending a lot more time with my uncle, much of that time period felt like being regularly slammed in the head with something painful and then needing to turn around to make sure the person who just smashed me was OK.

To be frank, most of having cancer seemed to be about the care of others. People who were so distressed when I told them, I had to hold their hands and tell them it would be ok. People whose response was to tell me of a friend that had a similar diagnosis, often ending with, “… oh and then they didn’t make it,” and me asking, “and why did you think telling me this was a good idea?” I suspect that everyone who has ever had cancer experiences the really weird things people tell you. Part of my memory of that time is of me, peeled slightly away from reality with the colours a bit dimmed and the lighting off, listening to people interacting with me, but really not with me. It was a dissociative stance, I suppose, but I can feel myself making the same expression now, and I am leaning away from the keyboard, puzzling out the oddities of it all.

A lot of shit happened. Some friends disappeared — also normal, my husband whom I had been wanting to divorce lost his mind and tried to steal all my money and demand that I go through all kinds of hoops to get through this. At the time, NYC was NOT a no fault divorce state. In my opinion, he was entirely at fault through dint of being a grasping asshole, but that wasn’t one of the options and would have required going to court. He held me entirely responsible for his not getting the green card he wanted, even to the degree of accusing me of going behind his back to the USCIS to somehow block this. Can you feel the crazy? I can, but I can’t lean any further away from this machine and have my fingers reach the keys. I can, however, also feel that anxiety pooling up in my chest, that feeling of being trapped and having no way out.

After I finished treatment the doctors waved their congratulations and disappeared. Years later I learned I should have had mental health assistance — cancer along with heart attacks cause significant post-treatment depression cycles. I was already probably deeply in one during treatment and my doctors should have noticed, based on what I was telling them, but nothing came of it. I also learned, years later, that at the time they did NOT prescribe mental health support lest us women (specifically) convince ourselves we are depressed and demand treatment from an overburdened system. Apparently as well I should have begun physical therapy, because the extensive internal scarring from three surgeries limited my motion. I have no idea why this never came up nor was it suggested. When I finally started dealing with it, eight or nine years later, every PT and otherwise person I saw was a mix of horrified and astonished, and also sorrowful because having waited that long, it would be nearly impossible to return me to something near my original form.

Unlike the XKCD comic, however, I never really managed to find my way back to believing I was going to live, for at least the first decade. I had decided full stop I would never undergo treatment again, so after the first few years of check-ups every three to six months, I simply stopped going. I could not settle back into work or do things I disliked, but I also could not choose to do something hard that I love that could take years, because I didn’t expect to live that long. Not on the surface, but deep inside, in the way that behaviors seem to just happen, and it took me a long time to think them through.

Thinking about the last fifteen years, if I could pop back, to cancer treatment, not to the before, there are so many changes I’d make in how I chose to live my life. It’s irrational to think if I popped back I’d suddenly have the energy and agency to make them — I was exhausted for a good five or six years post treatment, but I like to consider.

I find me now wondering if I went back and did things differently, where would that trajectory have taken me, would I still want to end up at that place in my life, and what is the fastest way to traverse the glacier and the massive cracks to get myself back to a place like that. If this is what I want.

Foolishness, of course. It doesn’t work like that, and the better question would be, where do I want to go now, what do I understand from all that crap that happened, and what I would have wanted to be different, to move into the place I want to be now. I think, weirdly, cancer treatment and the aftermath broke my ability to dream. I recognize this, but I am not sure I have fully recovered it. I find I am still able to easily pop into the post-C crisis mode I used to refer to as dragon-state: I wish to hoard, money, people, books, shoes, dresses, and sit alone on them in a cavern where no one can get to me. Pretty unhealthy. But also funny. I think it would be better to be a sociable dragon. I could use the claws and teeth and fire. And the sense of safety I imagine I would have if I were a dragon instead of what I sometimes feel like, just a girl, in a world that is hostile to girls.

I finished treatment near my birthday and invited the women who had supported me through it, 14 absolutely wonderful people, to dinner in NYC. It was incredible and I could see that one deep and internal thing in me had changed through the process, I was more willing to ask for help, to be present with people, to not always insist on being the edge-girl observer. My friend Sara created a book for me, each person put in a photo of us together, and wrote a note, and Sara, crafty designer that she is, made it beautiful. I pulled it out today, I still love all these women, though I’ve not been great about being in touch. A little too much lonely dragon in the dark but without her hoard. (Except the shoes, there are so many shoes, still.)

There were amazing men as well, Seth and James in particular, but for that dinner, it was all the ladies.

Everything crooked can be straightened. Every path can be regained. I have always felt, even when not acting, that the future can be anything I want, if I dream and if I reach for it. I have this image in my mind that I wish to draw on my chalkboard wall. The path I took, the path I’d have preferred, and the path of now, with all the dreamed of outcomes sparkling at the end, with all my friends and full of love and interesting things and creativity and tasty things to eat and drink. Not sure I’d buy more shoes though.

I’d like to write the real stories, the terrible things. They are funny and horrible and awe inspiring (and not in a good way), yet something in me feels they should be spoken. I had a blog at the time, called TIBY (the yellow blight), full of rage and frustration, which would make good interludes, but the stories of how people manage the frailties and weaknesses of others, at least in my worlds, can be very dark. Or more precisely, how people handle their own frailties and weakness in light of things that scare them, that they cannot control, is not always grand.

I am happy for Randall and his girlfriend that their fifteen years has found them in a place of love and happiness, alive, together, and hopefully still taking photos of crocodiles and falling into the holes that sometimes open in the post-cancer world, but fishing each other out.

I shall fish me out, of this thesis, of the past, into the boats, and across the water.